| Version 8 (modified by Giersch, 9 years ago) (diff) |

|---|

Discretization

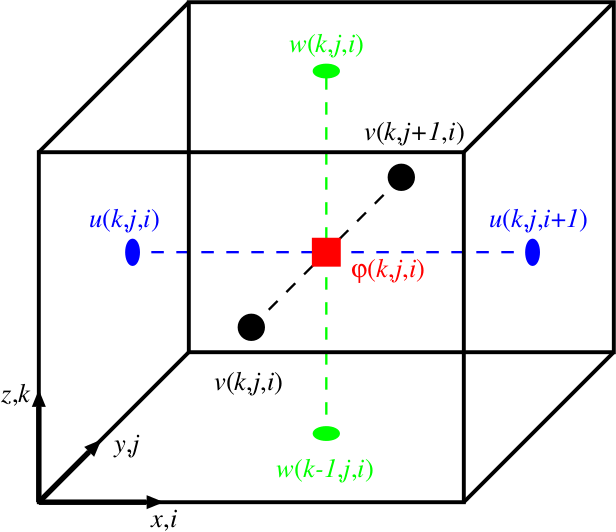

The model domain in PALM is discretized in space using finite differences and equidistant horizontal grid spacings (Δx, Δy). The grid can be stretched in the vertical direction well above the ABL to save computational time in the free atmosphere. The Arakawa staggered C-grid (Harlow and Welch, 1965; Arakawa and Lamb, 1977) is used, where scalar quantities are defined at the center of each grid volume, whereas velocity components are shifted by half a grid width in their respective direction so that they are defined at the edges of the grid volumes (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The Arakawa staggered C-grid. The indices i, j, k refer to grid points in x, y and z direction, respectively. Scalar quantities φ are defined at the center of the grid volume, whereas velocities are defined at the edges of the grid volumes.

It is thus possible to calculate the derivatives of the velocity components at the center of the volumes (same location as the scalars). By the same token, derivatives of scalar quantities can be calculated at the edges of the volumes. In this way it is possible to calculate derivatives over only one grid length and the effective spatial model resolution can be increased by a factor of two in comparison to non-staggered grids. By default, the advection terms in the first five equations in Sect. governing equations are discretized using an upwind-biased 5th-order differencing scheme in combination with a 3rd-order Runge–Kutta time-stepping scheme after Williamson (1980). Wicker and Skamarock(2002) compared different time- and advection differencing schemes and found that this combination give the best results regarding accuracy and algorithmic simplicity. However, the 5th-order differencing scheme is known to be overly dissipative. It is thus also possible to use a 2nd-order scheme after Piacsek and Williams(1970). The latter scheme is non-dissipative, but it suffers from immense numerical dispersion. Time discretization can also be achieved using 2nd-order Runge–Kutta or 1st-order Euler schemes.

Higher order advection scheme

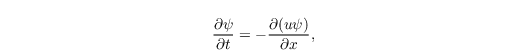

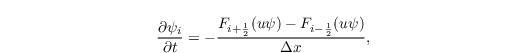

Based on a flux formulation of the advection term

the one dimensional advection equation can be written in the following semidiscrete form:

where

denotes the fluxes staggered half a grid length related to the advected quantity.

Wicker and Skamarock (2002) discretized the 6th and 5th order fluxes as follows:

![\begin{align*}

F_{i-\frac{1}{2}}^{6} = \frac{u_{i-\frac{1}{2}}}{60} \left[ 37(\psi_{i}+\psi_{i-1}) - 8(\psi_{i+1} + \psi_{i-2}) +(\psi_{i+2} + \psi_{i-3}) \right] ,

\end{align*}](/trac/tracmath/ea3d33d8e13c34a7cae7976bf9a7068b4d0ddee9.png)

![\begin{align*}

F_{i-\frac{1}{2}}^{5} = F_{i-\frac{1}{2}}^{6} - \dfrac{|u_{i-\frac{1}{2}}|}{60} \left[10(\psi_{i}-\psi_{i-1}) -5(\psi_{i+1} - \psi_{i-2})+(\psi_{i+2} - \psi_{i-3}) \right] .

\end{align*}](/trac/tracmath/444d2f6a945150702636d75fd29e1dedcbf696e1.png)

The 5th order upwind discretization (WS5) consists of a centered non dissipative 6th (WS6) order flux and an artificially added numerical dissipation term. This term is necessary to stabilize the numerical solution, because higher order centered fluxes exhibits worse stability properties. The absolute value of the advective velocity component in the dissipation term removes a sign-dependent effect of the velocity and assures a dissipative effect also for u < 0.

Numerical properties

A semidiscrete fourier transformation for the spatial derivatives maps the one dimensional advection equation in fourier space as follows (Baldauf, 2008):

where

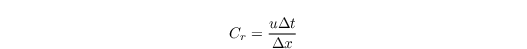

denotes the fourier transformed of ψ. The Courant number

characterizes stability properties and i is the imaginary unit. κeff is the effective wavenumber of a mode in fourier space and characterizes the modified wavenumber through the discretization. The real part of the effective wavenumber describes the dispersion error, the imaginary part the dissipation error.

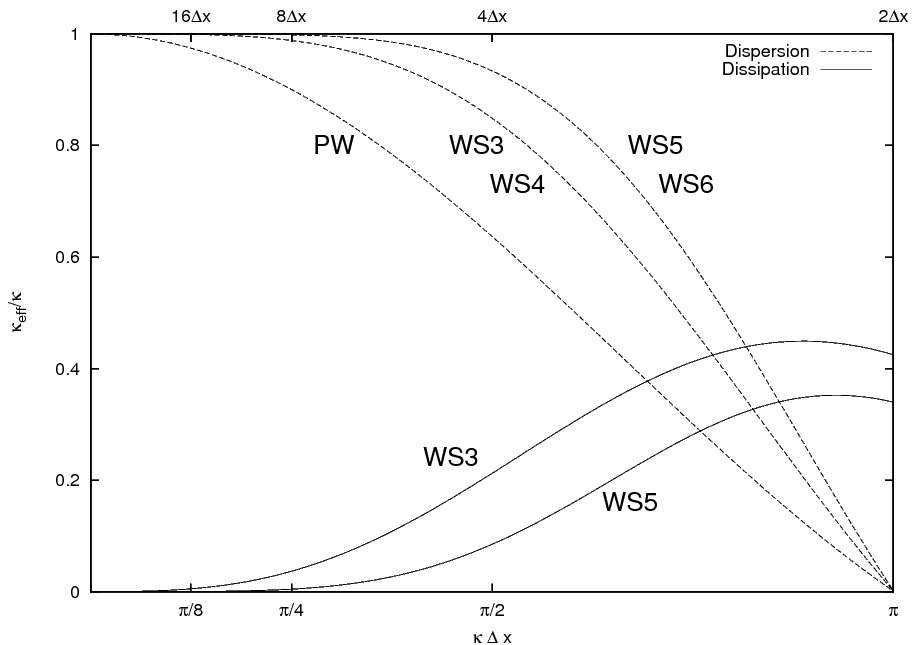

Fig. 5 shows the dispersion and dissipation error as a function of the dimensionless wavenumber κ Δx for WS3 (3rd order scheme), WS4 (4th order scheme), WS5, WS6 and the 2nd order scheme of Piacsek and Williams (1970) (PW). The dispersion error of the upwind schemes and the dispersion error of the next higher, even ordered scheme are identical. Generally the dispersion error decreases with increasing order of the discretization. However, no of the depicted schemes is able to adequately resolve structures with wavelengths near 2-Δx (generally no scheme based on finite differences is capable to do this). The centered, even ordered schemes hold no dissipation errors. With increasing order the numerical dissipation is more local. So the maximum wavelength affected by the dissipation term is round about 8-Δx with WS5, whereas wavelength of 16-Δx are still affected with WS3. Accordingly to the maximum of the amplification factor at κ Δx = 1.69 (these waves become unstable at first) in conjunction with the used Runge-Kutta method (Baldauf, 2008), the 5th order dissipation is sufficient to avoid instabilities. The maximum stable Courant-number is Cr = 1.4 (Baldauf, 2008).

Note: A stable numerical solution can only be guaranteed with the 3 rd order Runge-Kutta method.

Boundaries

Due to the large stencil of WS5, additional ghost layers are necessary on each lateral boundary of each processor subdomain to avoid local data dependencies. Therefore, the exchange of ghost layers is adapted to a dynamic number of ghost layers. For the bottom and top boundaries, lateral non-cyclic boundaries as well as near topography walls the order of the discrertization is successively degraded from WS5 to WS3 to a 1st order scheme. The degradation is controlled by three-dimensional bit flags, where several bits mark the order of the advection scheme in the x-, y-, and z-direction. Technically, in case of topography, advective fluxes are calculated for the first-, third-, and fifth-order discretization at each grid point, while the respective bit controls which discretization is finally used. In the following, the respective flags are listed:

| Array | Bit | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

wall_flags_0 | 0 | scalar advection in the x-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 1 | scalar advection in the x-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 2 | scalar advection in the x-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 3 | scalar advection in the y-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 4 | scalar advection in the y-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 5 | scalar advection in the y-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 6 | scalar advection in the z-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 7 | scalar advection in the z-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 8 | scalar advection in the z-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 9 | u advection in the x-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 10 | u advection in the x-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 11 | u advection in the x-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 12 | u advection in the y-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 13 | u advection in the y-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 14 | u advection in the y-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 15 | u advection in the z-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 16 | u advection in the z-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 17 | u advection in the z-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 18 | v advection in the x-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 19 | v advection in the x-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 20 | v advection in the x-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 21 | v advection in the y-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 22 | v advection in the y-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 23 | v advection in the y-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 24 | v advection in the z-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 25 | v advection in the z-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 26 | v advection in the z-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 27 | w advection in the x-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 28 | w advection in the x-direction: third order |

wall_flags_0 | 29 | w advection in the x-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_0 | 20 | w advection in the y-direction: first order |

wall_flags_0 | 31 | w advection in the y-direction: third order |

wall_flags_00 | 0 | w advection in the y-direction: fifth order |

wall_flags_00 | 1 | w advection in the z-direction: first order |

wall_flags_00 | 2 | w advection in the z-direction: third order |

wall_flags_00 | 3 | w advection in the z-direction: fifth order |

Statistical evaluation of turbulent fluxes

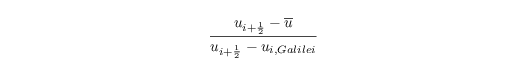

The statistical evaluation of turbulent fluxes should be consistent with the discretization in the prognostic equations because otherwise some unphysical effects occur. For example the computation of the turbulent fluxes as variances and covariances induces some conspicuous kinks in the vertical heat and momentum fluxes near the surface, while the temperature and velocity profiles show no conspicuity. In order to compute the turbulent fluxes as they appear in the prognostic equations, the fluxes are computed in the advection routines, buffered and then reused for the statistics. To receive the turbulent and not the mean signal and to remove the influence of Galilei transformation, the centered fraction of the flux Fi+1/2 has to be multiplied with a factor

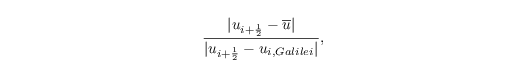

and the dissipative fraction with a factor

where u denotes the corresponding velocity component. Furthermore, the turbulent fluxes are evaluated on each Runge-Kutta substep and weighted with the respective Runge-Kutta coefficients to remove dependencies of the Runge-Kutta substeps. The interpretation of the turbulent fluxes as variances and covariances is no longer valid when using WS5. For other advection schemes, like the PW-scheme, the interpretation of turbulent fluxes as co/variances is still valid, because the discretization is alike the computation of the co/variances.

References

- Harlow FH, Welch JE. 1965. Numerical calculation of time-dependent viscous incompressible flow of fluid with free surface. Phys. Fluids 8: 2182–2189.

- Schumann U. 1977. Computational design of the basic dynamical processes of the UCLA general circulation model. in: General Circulation Models of the Atmosphere, Methods in Computational Physics. edited by: Chang J. 17. Berlin. 173–265.

- Williamson JH. 1980. Low-storage Runge–Kutta schemes. J. Comput. Phys. 35: 48–56.

- Wicker LJ, Skamarock WC. 2002. Time-splitting methods for elastic models using forward time schemes. Mon. Weather Rev. 130: 2088–2097.

- Piacsek SA, Williams GP. 1970. Conservation properties of convection difference schemes. J. Comput. Phys. 198: 580–616.

- Baldauf, M. 2008 Stability analysis for linear discretisations of the advection equation with Runge-Kutta time integration. J. Comput. Phys. 227: 6638-6659.

Attachments (2)

- 02.png (25.3 KB) - added by Giersch 9 years ago.

-

prop.png

(26.1 KB) -

added by Giersch 9 years ago.

The dispersion and dissipation error of the different advection schemes as a function of the dimensionless wavenumber

Download all attachments as: .zip